Teddy Eyster

UBC Masters Program in Resources, Environment, and Sustainability

Arriving at Blachford Lake, land of the Dene

After a day of travel from Vancouver to Yellowknife, I arrived at Blachford Lake Lodge by floatplane. There are no summer roads to the lake and all supplies, gear, and people must come in and out with a 25-minute flight to Yellowknife. Flying over the country from Yellowknife gave me a glimpse at what the land here looks like in summer–lush meadows, a multitude of lakes ringed in vegetation, spruces marching up small hills with exposed granite domes. When seen from above, the landscape is a juxtaposition of water and rock. It reminded me of a mountain landscape, only one where the peaks have been replaced with lakes.

Upon arrival, I met the other students—students from UBC studying First Nations and Indigenous Studies, educators from California, eastern Canada, and Harvard. We had a brief orientation to the lodge, before sitting down to a hearty dinner prepared by the lodge’s staff. After dinner, we gathered at a fire on the ridge to give thanks to the land and all those who had come before us. We introduced ourselves and our hopes for the week, and some introduced themselves in their own Indigenous languages. For me, as the descendant of American settlers, finding my place within this space and on the land of the Yellowknives Dene was part of my wish. As the evening drew later, the sun still rode high in the sky giving time a different meaning and reinforcing the feeling that I was somewhere new.

We were busy on our first full day at Dechinta with activities to set up camp and begin our transition to living on the land of the Dene. Together we set up a canvas tent to be our classroom, collected ori (spruce boughs) and wove it into a floor, strung up moose hides on racks, and set a gill net to catch fish. The atmosphere was lively and cooperative despite the occasional swarm of mosquitoes that swirled about our ankles. Growing up I heard people talk about “living off the land” meaning to get sustenance, shelter, and other needs from natural landscapes—an equivalent to off the grid. I think it is non-trivial that the folks at Dechinta talk about living and learning “on the land” to describe what in some ways might require a similar skillset of self-sufficiency. Living on the land also acknowledges the importance of the land itself and moves the emphasis from the individual taking to the landscape giving.

Later in the day, we gathered in the shade of the tent, supported by spruce boughs, and talked about the importance of context. I learned that Anishinaabe story telling is less about the content of the words or story and more about the context in which it is told–this concept of context seems to be a larger thread that runs through what I learned about Dene culture as well. The significance of an action, person, or event is reliant upon the relationships surrounding it. Nothing exits in a vacuum and the land and water are the base on which all else rests. For example, when the Dene tell the size of a fish or object it is displayed with one hand on the other arm (thus relative to the person), rather than the western gesture with empty space between one’s hands. This idea extends to land itself. One of the instructors, Leanne Betasamosake Simpsoncommented that “land is relational.” This runs counter to many western concepts of land ownership, transfer, and value. This is especially true in the land of the Dene where the concepts of the word Dene itself can be translated into English as “the people flowing from the land.”[1]

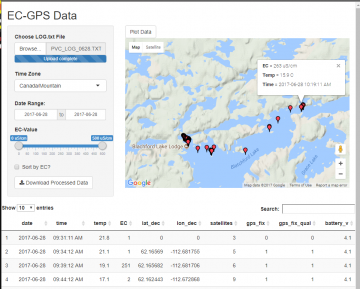

Logger prototype under development to screen for temperature and electrical conductivity abnormalities as a result of extractive industry contamination. The logger records values and GPS locations to a memory card that can be later evaluated to target areas for follow-up testing.

Logger prototype under development to screen for temperature and electrical conductivity abnormalities as a result of extractive industry contamination. The logger records values and GPS locations to a memory card that can be later evaluated to target areas for follow-up testing.

Western Water Monitoring and Traditional Knowledge

In part, my trip to Dechinta was to test a datalogger we are developing to screen for extractive industry contamination in water. On the way to check the gill nets for fish on the second day, we pulled two sensors behind our aluminum skiff. Being out on the water was exhilarating and also allowed me to trouble shoot the weight of the sensor, how fast the boat went, and catch errors in the logger’s programming.

I was lucky to have help with the logger from one of the instructor’s children. He kept the unit from bouncing around on the bumpy boat ride.

I was lucky to have help with the logger from one of the instructor’s children. He kept the unit from bouncing around on the bumpy boat ride.

One day on our way back from the nets I asked one of the instructors, “Why did we come so far across the lake to set the nets?” He replied that it’s deeper than other parts of the lake and is a good place for trout. When I asked about the source of the information, he said “Oh, local knowledge…” When I looked at the sensor results, I saw that the area surrounding the net was colder than other areas of the lake. This cooler temperature complements the information that the lake is deeper there, as deep waters take longer to warm than shallower ones. This is not a validation for the traditional knowledge — traditional knowledge stand on its own—but it is an important example of how traditional knowledge can guide data interpretation. Data has no meaning on its own, without context and comparison a temperature, or number is no more than an abstraction. While western science often seeks to interpret data by starting with the numbers, by starting with the stories and knowledge of people on the land a much richer story develops.

A screen capture from the user interface for the datalogger. Locations are displayed on a map along with temperature and electrical conductivity values.

A screen capture from the user interface for the datalogger. Locations are displayed on a map along with temperature and electrical conductivity values.

Indigenous Art and Public Schools

The Short Course program at Dechinta is designed to promote education both on the land with indigenous skills and academically through lectures and discussions. On our third morning, we learned about contemporary indigenous art. Leanne Betesamosake Simpson shared her creative process in developing her newest poetic musical collaboration with indigenous artists and filmmakers f(l)ight. I was particularly struck by her piece “The oldest Tree in the World” where she explores her relationship with the oldest sugar maple, a tree in her territory–especially as it related to our other discussions about relationships between people and the land. When I was in high school English class, the teacher asked that we write an essay about a meaningful relationship and how it affected us. I chose to write about a tamarack tree in our back yard that I sat under in the mornings before school. Several days after I submitted the essay the teacher told me I’d have to re-write the essay on a different topic. She said that I could not have a meaningful relationship with a tree because it couldn’t respond. I’d never seriously considered the role of public schools in isolating people from the land, but now I see that part of western pedagogical culture which puts people in boxes, and doesn’t allow significant relationships with the natural world.

Roasting dryfish on the fire.

Roasting dryfish on the fire.

The Giant Mine and arsenic trioxide contamination in Yellowknife

In addition to learning about explicitly Indigenous issues we also learned about environmental issues surrounding resource extraction through the documentary film Shadow of a Giant. The town of Yellowknife was built around mineral extraction. In 1948 the Giant Mine began operation to process gold ore. As a result of the refining process, the mine produced large amounts of toxic arsenic trioxide. For the first three years, this non-threshold carcinigen spewed out of the smoke stacks and was deposited across the region. After scrubbers were installed, the mine began storing the arsenic waste underground in bunkers inadequate to the task.

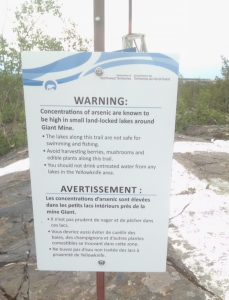

A sign warning of arsenic toxicity near a small lake outside of Yellowknife.

A sign warning of arsenic toxicity near a small lake outside of Yellowknife.

On my way back to Vancouver I stopped in Yellowknife and saw a newly installed sign to advertise the toxicity of a nearby lake saying: “Avoid harvesting berries, mushrooms, and edible plants along this trail.” This is how the greed of a few affects the well being of all. Since its opening, the Giant mine created wealth for investors but also created poison and disease for people in the area—forcing them to choose between their traditions and their health. At this point there are no real solutions and there is no one left to hold accountable for the recklessness of the past. But even knowing the toxicity of our actions, people continue to pollute their environment. On a small outcrop above Yellowknife I witnessed a plume rising into the sky. What will it take until we learn?

Learning Canadian History and My Place in It

I am a newcomer to Canada. I moved to Vancouver in the fall of 2016 to begin a master’s program in environmental studies. Growing up I learned little of the history of Native Americans in the US and even less about First Nations history in Canada. My time at Dechinta brought historical context to the present moment–speaking with an Elder who attended residential school and was forcibly removed from the land, hearing stories from a peer whose family was relocated by the federal government under false promises, and seeing the results of Canadian policies designed to promote resource extraction. I’ve gained a new appreciation for the country in which I’m living. I’m aware that acknowledging the territorial land rights of the Musqueam FN at UBC is more than a formality. And, I hope I’m beginning to learn how to engage in respectful dialog with people of both settler and Indigenous roots.

Moosehide tanning with fishlivers. When I was young I was fascinated by indigenous skills and learned to tan deer hides from books and “survival skill” enthusiasts.

How Academics, the Environment and Land-based Skills Join

In reflection, I found something surprising at the Dechinta field school. Three separate parts of my life came together for the first time: my academic interest in water monitoring and hydrology, my ethical interest in protecting the natural environment, and my personal fascination with land-based skills and traditional knowledge. I hope that my experience with Dechinta will be one of many that fuse my interests and provide a platform for good and a space for me to learn about the history of people on and land and how to be a better steward of the landscapes I inhabit.

[1] Lecture on Dene Chanie, or The Sacred Path, by Siku Allooloo, July 1, 2017

PROTOTYPE DE L’Enregistreur de donnée en cours de développement qui analyse les anomalies de températures et de conductivité électrique qui découle de contamination reliée a l’industrie extractive. L’APPAREIL ENREGISTRE les valeurs et les locations gps sur une carte mémoire qui peut être évaluée afin de tester des zones sensibles à tester.

PROTOTYPE DE L’Enregistreur de donnée en cours de développement qui analyse les anomalies de températures et de conductivité électrique qui découle de contamination reliée a l’industrie extractive. L’APPAREIL ENREGISTRE les valeurs et les locations gps sur une carte mémoire qui peut être évaluée afin de tester des zones sensibles à tester.

une capture d’écran de l’interface utilisateur. les locations sont représentées sur un plan, accompagnées des valeurs réciproques en termes de température et de conductivité électrique.

une capture d’écran de l’interface utilisateur. les locations sont représentées sur un plan, accompagnées des valeurs réciproques en termes de température et de conductivité électrique. NOUS RôTISSONS LE POISSON SEC SUR LE FEU.

NOUS RôTISSONS LE POISSON SEC SUR LE FEU. UN PANNEAU D’avertissement sur la présence de trioxyde de d’arsenic près d’un petit lac à la sortie de yellowknife

UN PANNEAU D’avertissement sur la présence de trioxyde de d’arsenic près d’un petit lac à la sortie de yellowknife