Tamar Meshel – International Law Affecting Canada’s Jursidiction Over Water

Tamar Meshel – International Law Affecting Canada’s Jursidiction Over Water

We asked 3 Decolonizing Water Research Assistants to reflect and write about their time at the Anishinaabe Nibi (Water) Gathering 2018.

Jacquie Tourand

Driving from the Winnipeg Airport to the Gathering site was my first introduction to Manitoba. The landscape was so different from the West Coast; the trees were a different kind of green and there was no moisture in the air. There were no mountains to cradle you in their embrace and I felt so exposed. But then the skies lasted forever and it was its own breathtaking kind of beauty.

Driving from the Winnipeg Airport to the Gathering site was my first introduction to Manitoba. The landscape was so different from the West Coast; the trees were a different kind of green and there was no moisture in the air. There were no mountains to cradle you in their embrace and I felt so exposed. But then the skies lasted forever and it was its own breathtaking kind of beauty.

The day before the Gathering was to start I helped build the Teaching Lodge. Peter and his daughter directed the building efforts. Her own children reminded me of my nieces and nephews back home and made me think how our lives truly are built on the relationships we have with each other. Building the lodge was physical work and it was a very hot, dry day. Drinking the cold water that several ladies brought overwas a gift. My favourite part of the endeavour was when everyone came together to pull the tarp over the entire structure. It just felt so good to be part of something larger than myself. That we were all working towards a common goal.

During the Gathering, there were multiple ceremonies. It was really emotional and powerful to listen to people share their stories. They aren’t mine to tell, but the lessons learned will stay with me. Especially during the woman’s circle; it was so important to hear from woman from all over share their accomplishments and perhaps more importantly their struggles so freely and so openly. I want to be as strong and as vulnerable as these women were and to be that for others.

Near the end of the Gathering, I went with a group of others to the petroforms nearby. I walked with an older woman from Manitoba and we talked about how incredible it was that we were here, the result of generations of people living lives we’ll never know. It really hit home looking at the petroforms, how what we do today will ripple out towards the future, beyond what we can truly understand or imagine. We shared stories about our lives and our families and shared an intense moment as we each spoke of the difficulties we’ve encountered. We hugged and cried together. In that instant I loved her. We’ve exchanged contact details and I plan on visiting her.

Up until the Gathering, I had never really considered the role that water has taken in my life. The Anishinaabe Nibi Water Gathering has truly challenged how I relate to water. From the tea I drink, to the showers I take, to the water that nourishes the trees, plants,and animals around me that I love so much, I have realized how much water has been there for me in my life. When I was a little girl, I was sexually assaulted at a pool and became afraid of being in water. But I found comfort in bathing and how water would wash away all the negativity, the shame, and the feelings that stuck to my skin and hair. Even when I was scared or angry with water, the water was there for me. She loved me even then.

For me, the Gathering was a time of listening, learning, and reflection. I am grateful for the experience and I have left with a renewed sense of hope. So me of the takeaways that I’ve learned are: the importance of sharing knowledge, especially cultural knowledge and language; the importance of reaching out to others and sharing struggles together and of not being embarrassed or ashamed of having feelings; and most importantly, how much water takes care of us and our responsibility to take care of her in return.

me of the takeaways that I’ve learned are: the importance of sharing knowledge, especially cultural knowledge and language; the importance of reaching out to others and sharing struggles together and of not being embarrassed or ashamed of having feelings; and most importantly, how much water takes care of us and our responsibility to take care of her in return.

Myia Antone

nilh ta ents Myia Antone kwi en sna. tina7 chan Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Stá7mes úxwumixw.

nilh ta ents Myia Antone kwi en sna. tina7 chan Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Stá7mes úxwumixw.

Coming home from the Anishinaabe Nibi Gathering 2018, I have so much to reflect on. My heart and spirit are full of the teachings I received and new friends I made. Visiting Manitoba for the first time, we spent 6 days on Treaty 3 lands and waters and after landing, I instantly felt a difference from being on the west coast. The land holds different stories, different memories.

The first day was spent with a smaller crowd, setting up and preparing for the gathering. Wearing our ceremonial skirts, we had a group of youth climbing ladders and tying poles together to help prepare the Midewiwin lodge. Following that, each day consisted of songs and teachings that honour the water. The gathering site was beautiful but a space takes its shape from the energy of the people who gather there. It was when everyone arrived that the space really became beautiful. We started everyday in a good way and met in ceremony. The lodge nurtured relationships and created a community.

One day, during a women’s support circle, a storm erupted and rain poured from the skies and thunder pounded through our bodies. Chaos erupted as everyone ran for cover and I bumped into an elder finding a safe home to place her tobacco offering for the thunderbirds. She reminded me to be grateful for blessings of the thunderbirds and the strength and power of Mother Earth. It had been very dry in Manitoba and everyone was relieved for the water. As we rushed back to our cabin to keep dry, I felt a bit homesick. The warm rain felt like a hug from my ancestors, reminding me of my west coast roots and that every living being on this Earth deserves water. We all need that water to dig our roots even deeper, grow taller and bloom every year.

I am grateful for this moment in time, when I’ve been gifted opportunities to cross paths with individuals that speak to my heart and nourish my being. I’m grateful for spaces like this gathering that celebrate the water protectors and hold up community as places of resistance and resurgence. In the most gentle way, I felt the presence of my ancestors and the presence of the ancestors of those lands and waters join us in ceremony.

I left Manitoba wondering what my responsibility and accountability to bear witness these stories and how will my actions reflect the stories I heard. I came home with a nourished mind, body and spirit. I feel stronger to continue in the fight to protect my traditional lands and waters for my future children and grandchildren. I want t

o take a moment and raise my hands up with so much love and respect to all my relations involved in carving out such an important space and giving me the opportunity to take part in it.

I am constantly thinking about the words of elder Peter Atkinson, “water will never cease to flow, when we hold it up.” This speaks to our responsibility as water protectors to hold up water, as water is life. We are reminded that Creation is dynamic. It continues to live on, even after we do. But that is only possible if we protect her. This is so important because when you take care of Mother Earth, she takes care of you.

chen wa kwélulusnitúmi ti txwna7na.

Adèle Therias

Anishinaabe Nibi Water Gathering: Witnessing Resilience

As a research assistant for the Decolonizing Water Project, I was fortunate to attend the 2018 Anishinaabe Nibi Gathering this May. Having had a decidedly urban and global upbringing, I was humbled to meet people and hear teachings grounded in meaningful relationships to the land and to each other. I was immersed in another culture, and I am grateful to have taken part in Anishinaabe ceremonies and learned some principles of Anishinaabe Law. Being a descendant of European settlers, I felt my ancestors lean in as I witnessed powerful Indigenous resilience to Canada’s colonial past and present. Considering that my research outside of Decolonizing Water focuses on community resilience, it was eye-opening to see examples of the powerful work that is happening in Indigenous communities. When we returned from the trip, I struggled with the sudden sensory overload and the change of pace in the city, but I have been working to bring my learning with me and apply it in my work as I move forward.

The gathering reminded me of a family reunion from my childhood: it was multi-generational, we shared good food and, while some people did not know each other, everyone belonged there. I was struck by the respect and priority given to the elders, to whom we listened attentively and who were served their meals first. During ceremony, several babies and children would often be crawling and walking around, endlessly curious and encouraged to explore. It was evident from the first moment that each person had a responsibility in shaping the gathering, whether building the ceremonial lodge, watching the fire overnight, leading workshops or serving food. The men and the women were celebrated for their roles, and I was reminded of how positive intention and shared responsibility can create a healthy community, whether a family or a village.

Anishinaabe Nibi gathered people from different Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities, at different stages of learning about our identities and cultures. We shared space, words, and sacred experiences that helped me better understand how to be a respectful ally. I learned about the strength that can come from spiritualism, the belonging that is cultivated through ceremony, and the fight that is happening every time someone reconnects with their language. I learned about forms of resurgence that surprised me and left me in awe: Kacey Adams taught us to create bowls from clay harvested from the riverbed and how to conduct a firing ceremony. She explained that the clay tradition is one that was lost among previous generations but it has been traced and recreated with the help of archaeological records and experimentation. I learned about the power of resurgence that is grounded in love, with a deep respect for the land and water.

The gathering brought me new perspectives on knowledge. Fred explained that knowledge is within and learning is just gaining insight into what we already know. This understanding emphasizes the importance of those who came before in shaping what we experience today, and the process of sharing knowledge becomes just as important as the knowledge itself. As a result, I have begun reaching back to hear my own ancestors’ stories to better understand the history and legacy of my family. I also learned about the knowledge that is carried in each water droplet, and in the water that makes up the majority of our bodies. On the last day of the gathering, Laura taught the youth a song to carry with us into the future. She emphasized the importance of truly knowing things, rather than writing them down and forgetting them. Well, I will never forget the experience of sitting around her and repeating this song. Repeating it until the words were embedded into our minds. Repeating it until our hearts matched the beat of the drum.

Aimée Craft, University of Ottawa Faculty of Law Laurie Chan, Canada Research Chair in Toxicology and Environmental Health

Shifting the Framework of Canadian Water Governance through Indigenous Research Methods: Acknowledging the Past with an Eye on the Future.

by Rachel Arsenault, Sibyl Diver, Deborah McGregor, Aaron Witham and Carrie Bourassa

Journal: Water

Published January 10, 2018

Full Text: Here

Abstract: First Nations communities in Canada are disproportionately affected by poor water quality. As one example, many communities have been living under boil water advisories for decades, but government interventions to date have had limited impact. This paper examines the importance of using Indigenous research methodologies to address current water issues affecting First Nations. The work is part of larger project applying decolonizing methodologies to Indigenous water governance. Because Indigenous epistemologies are a central component of Indigenous research methods, our analysis begins with presenting a theoretical framework for understanding Indigenous water relations. We then consider three cases of innovative Indigenous research initiatives that demonstrate how water research and policy initiatives can adopt a more Indigenous-centered approach in practice. Cases include (1) an Indigenous Community-Based Health Research Lab that follows a two-eyed seeing philosophy (Saskatchewan); (2) water policy research that uses collective knowledge sharing frameworks to facilitate respectful, non-extractive conversations among Elders and traditional knowledge holders (Ontario); and (3) a long-term community-based research initiative on decolonizing water that is practicing reciprocal learning methodologies (British Columbia, Alberta).

By establishing new water governance frameworks informed by Indigenous research methods, the authors hope to promote innovative, adaptable solutions, rooted in Indigenous epistemologies.

Keywords: Indigenous research methods; water governance; Indigenous knowledge systems; Indigenous water relations; community-based research; reciprocal learning; environmental justice; boil water advisories; First Nations; Canada

Arriving at Blachford Lake, land of the Dene

After a day of travel from Vancouver to Yellowknife, I arrived at Blachford Lake Lodge by floatplane. There are no summer roads to the lake and all supplies, gear, and people must come in and out with a 25-minute flight to Yellowknife. Flying over the country from Yellowknife gave me a glimpse at what the land here looks like in summer–lush meadows, a multitude of lakes ringed in vegetation, spruces marching up small hills with exposed granite domes. When seen from above, the landscape is a juxtaposition of water and rock. It reminded me of a mountain landscape, only one where the peaks have been replaced with lakes.

Upon arrival, I met the other students—students from UBC studying First Nations and Indigenous Studies, educators from California, eastern Canada, and Harvard. We had a brief orientation to the lodge, before sitting down to a hearty dinner prepared by the lodge’s staff. After dinner, we gathered at a fire on the ridge to give thanks to the land and all those who had come before us. We introduced ourselves and our hopes for the week, and some introduced themselves in their own Indigenous languages. For me, as the descendant of American settlers, finding my place within this space and on the land of the Yellowknives Dene was part of my wish. As the evening drew later, the sun still rode high in the sky giving time a different meaning and reinforcing the feeling that I was somewhere new.

We were busy on our first full day at Dechinta with activities to set up camp and begin our transition to living on the land of the Dene. Together we set up a canvas tent to be our classroom, collected ori (spruce boughs) and wove it into a floor, strung up moose hides on racks, and set a gill net to catch fish. The atmosphere was lively and cooperative despite the occasional swarm of mosquitoes that swirled about our ankles. Growing up I heard people talk about “living off the land” meaning to get sustenance, shelter, and other needs from natural landscapes—an equivalent to off the grid. I think it is non-trivial that the folks at Dechinta talk about living and learning “on the land” to describe what in some ways might require a similar skillset of self-sufficiency. Living on the land also acknowledges the importance of the land itself and moves the emphasis from the individual taking to the landscape giving.

Later in the day, we gathered in the shade of the tent, supported by spruce boughs, and talked about the importance of context. I learned that Anishinaabe story telling is less about the content of the words or story and more about the context in which it is told–this concept of context seems to be a larger thread that runs through what I learned about Dene culture as well. The significance of an action, person, or event is reliant upon the relationships surrounding it. Nothing exits in a vacuum and the land and water are the base on which all else rests. For example, when the Dene tell the size of a fish or object it is displayed with one hand on the other arm (thus relative to the person), rather than the western gesture with empty space between one’s hands. This idea extends to land itself. One of the instructors, Leanne Betasamosake Simpsoncommented that “land is relational.” This runs counter to many western concepts of land ownership, transfer, and value. This is especially true in the land of the Dene where the concepts of the word Dene itself can be translated into English as “the people flowing from the land.”[1]

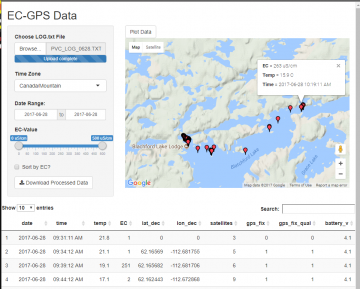

Logger prototype under development to screen for temperature and electrical conductivity abnormalities as a result of extractive industry contamination. The logger records values and GPS locations to a memory card that can be later evaluated to target areas for follow-up testing.

Logger prototype under development to screen for temperature and electrical conductivity abnormalities as a result of extractive industry contamination. The logger records values and GPS locations to a memory card that can be later evaluated to target areas for follow-up testing.Western Water Monitoring and Traditional Knowledge

In part, my trip to Dechinta was to test a datalogger we are developing to screen for extractive industry contamination in water. On the way to check the gill nets for fish on the second day, we pulled two sensors behind our aluminum skiff. Being out on the water was exhilarating and also allowed me to trouble shoot the weight of the sensor, how fast the boat went, and catch errors in the logger’s programming.

I was lucky to have help with the logger from one of the instructor’s children. He kept the unit from bouncing around on the bumpy boat ride.

I was lucky to have help with the logger from one of the instructor’s children. He kept the unit from bouncing around on the bumpy boat ride.

One day on our way back from the nets I asked one of the instructors, “Why did we come so far across the lake to set the nets?” He replied that it’s deeper than other parts of the lake and is a good place for trout. When I asked about the source of the information, he said “Oh, local knowledge…” When I looked at the sensor results, I saw that the area surrounding the net was colder than other areas of the lake. This cooler temperature complements the information that the lake is deeper there, as deep waters take longer to warm than shallower ones. This is not a validation for the traditional knowledge — traditional knowledge stand on its own—but it is an important example of how traditional knowledge can guide data interpretation. Data has no meaning on its own, without context and comparison a temperature, or number is no more than an abstraction. While western science often seeks to interpret data by starting with the numbers, by starting with the stories and knowledge of people on the land a much richer story develops.

A screen capture from the user interface for the datalogger. Locations are displayed on a map along with temperature and electrical conductivity values.

A screen capture from the user interface for the datalogger. Locations are displayed on a map along with temperature and electrical conductivity values.

Indigenous Art and Public Schools

The Short Course program at Dechinta is designed to promote education both on the land with indigenous skills and academically through lectures and discussions. On our third morning, we learned about contemporary indigenous art. Leanne Betesamosake Simpson shared her creative process in developing her newest poetic musical collaboration with indigenous artists and filmmakers f(l)ight. I was particularly struck by her piece “The oldest Tree in the World” where she explores her relationship with the oldest sugar maple, a tree in her territory–especially as it related to our other discussions about relationships between people and the land. When I was in high school English class, the teacher asked that we write an essay about a meaningful relationship and how it affected us. I chose to write about a tamarack tree in our back yard that I sat under in the mornings before school. Several days after I submitted the essay the teacher told me I’d have to re-write the essay on a different topic. She said that I could not have a meaningful relationship with a tree because it couldn’t respond. I’d never seriously considered the role of public schools in isolating people from the land, but now I see that part of western pedagogical culture which puts people in boxes, and doesn’t allow significant relationships with the natural world.

Roasting dryfish on the fire.

Roasting dryfish on the fire.

The Giant Mine and arsenic trioxide contamination in Yellowknife

In addition to learning about explicitly Indigenous issues we also learned about environmental issues surrounding resource extraction through the documentary film Shadow of a Giant. The town of Yellowknife was built around mineral extraction. In 1948 the Giant Mine began operation to process gold ore. As a result of the refining process, the mine produced large amounts of toxic arsenic trioxide. For the first three years, this non-threshold carcinigen spewed out of the smoke stacks and was deposited across the region. After scrubbers were installed, the mine began storing the arsenic waste underground in bunkers inadequate to the task.

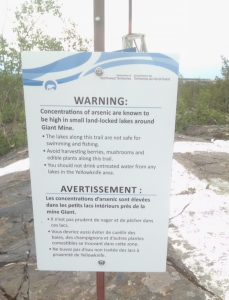

A sign warning of arsenic toxicity near a small lake outside of Yellowknife.

A sign warning of arsenic toxicity near a small lake outside of Yellowknife.

On my way back to Vancouver I stopped in Yellowknife and saw a newly installed sign to advertise the toxicity of a nearby lake saying: “Avoid harvesting berries, mushrooms, and edible plants along this trail.” This is how the greed of a few affects the well being of all. Since its opening, the Giant mine created wealth for investors but also created poison and disease for people in the area—forcing them to choose between their traditions and their health. At this point there are no real solutions and there is no one left to hold accountable for the recklessness of the past. But even knowing the toxicity of our actions, people continue to pollute their environment. On a small outcrop above Yellowknife I witnessed a plume rising into the sky. What will it take until we learn?

Learning Canadian History and My Place in It

I am a newcomer to Canada. I moved to Vancouver in the fall of 2016 to begin a master’s program in environmental studies. Growing up I learned little of the history of Native Americans in the US and even less about First Nations history in Canada. My time at Dechinta brought historical context to the present moment–speaking with an Elder who attended residential school and was forcibly removed from the land, hearing stories from a peer whose family was relocated by the federal government under false promises, and seeing the results of Canadian policies designed to promote resource extraction. I’ve gained a new appreciation for the country in which I’m living. I’m aware that acknowledging the territorial land rights of the Musqueam FN at UBC is more than a formality. And, I hope I’m beginning to learn how to engage in respectful dialog with people of both settler and Indigenous roots.

How Academics, the Environment and Land-based Skills Join

In reflection, I found something surprising at the Dechinta field school. Three separate parts of my life came together for the first time: my academic interest in water monitoring and hydrology, my ethical interest in protecting the natural environment, and my personal fascination with land-based skills and traditional knowledge. I hope that my experience with Dechinta will be one of many that fuse my interests and provide a platform for good and a space for me to learn about the history of people on and land and how to be a better steward of the landscapes I inhabit.

[1] Lecture on Dene Chanie, or The Sacred Path, by Siku Allooloo, July 1, 2017

New work by Quill Chistie!

New report co-authored with West Coast Environmental Law and the Decolonizing Water Project on the state of knowledge regarding UNDRIP, Free Prior and Informed Consent, and Fresh Water Resources in Canada.

Read Full Report here: Between Law and Practice

Listen to supporting podcasts on UNDRIP here!

Dr. Karen Bakker has been selected as a 2017 Trudeau Fellow: “Professor Karen Bakker and her team are working collaboratively with Indigenous communities, advisors, scholars, activists, and artists to exchange knowledge on how to decolonize water governance and improve water security for Indigenous peoples in Canada.”